In addition to elderly and disabled residents with low incomes and low asset levels, Medicaid is available to the following populations in Montana:

of Federal Poverty Level

Online at HealthCare.gov or at apply.mt.gov, or by phone at 1-800-318-2596.

Eligibility: Children are eligible for Medicaid with household income up to 143% of the federal poverty level (FPL), and CHIP with household income up to 261% of FPL. Pregnant women are eligible for Medicaid with household income up to 157% of FPL. Other adults are eligible for Medicaid with household income up to 138% of FPL (enrollment commenced November 2, 2015, for coverage effective January 1, 2016).

Yes, Montana’s Medicaid expansion took effect in January 2016, after CMS approved Montana’s Medicaid expansion waiver in late 2015. Under the expanded guidelines, Medicaid is available for all adults with incomes up to 138% of poverty; in 2024, that’s $20,782 for a single adult. (Medicaid and CHIP eligibility limits for children and pregnant women are higher, and remained unchanged by the waiver approval.)

Montana’s Medicaid expansion waiver (which included premiums for enrollees with income above 50% of the poverty level, although those were required to terminate at the end of 2022) came about as a result of Montana’s 2015 Senate Bill 405.

You can see more details below, but Medicaid expansion in Montana was initially approved through June 2019. Montana voters rejected an initiative in 2018 that would have permanently expanded Medicaid in the state and imposed a tobacco tax to fund the state’s portion of the cost.

In 2019, Montana enacted legislation that extended Medicaid expansion in the state for another six years, albeit with a work requirement. The state submitted the work requirement proposal to CMS in August 2019, but it was still pending when President Biden took office, and has not been approved. But Medicaid expansion is currently only approved in Montana through June 2025. The program will end at that point unless lawmakers approve another extension (or permanently expand Medicaid) during the 2025 legislative session. 2

We’ve created this guide to help you understand the Montana health insurance options available to you and your family, and to help you select the coverage that will best fit your needs and budget.

Hoping to improve your smile? Dental insurance may be a smart addition to your health coverage. Our guide explores dental coverage options in Montana.

Use our guide to learn about Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medigap coverage available in Montana as well as the state’s Medicare supplement (Medigap) regulations.

Short-term health plans provide temporary health insurance for consumers who may find themselves without comprehensive coverage.

If you are under 65 and don’t have Medicare:

If you’re 65 or older or have Medicare, visit this website to apply for Medicaid benefits.

Many Medicare beneficiaries receive Medicaid financial assistance that can help them with Medicare premiums, lower prescription drug costs, and pays for expenses not covered by Medicare – including long-term care.

Our guide to financial assistance for Medicare enrollees in Montana includes overviews of these programs, including Medicaid nursing home benefits, Extra Help, and eligibility guidelines for assistance.

From March 2020 through March 2023, states could not disenroll anyone from Medicaid, even if they no longer met the eligibility rules. But that changed as of April 2023, and states were required to redetermine Medicaid eligibility for everyone enrolled in the program, over the course of a year-long “unwinding” period.

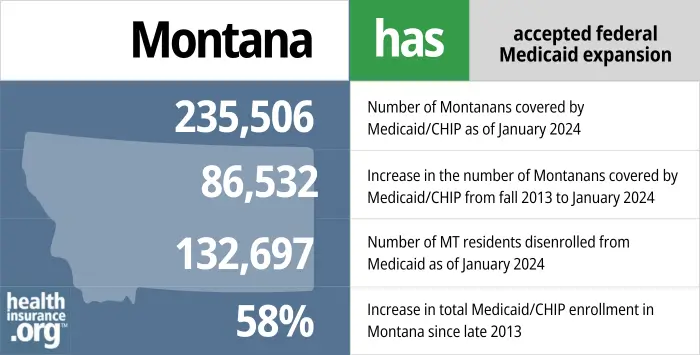

Montana began the unwinding process in April 2023, and their first round of disenrollments came at the end of May. By early 2024, almost 135,000 people had been disenrolled from Montana Medicaid/CHIP. Total enrollment had dropped from about 330,000 to about 230,000 by May 2024 7 (the net enrollment decline is smaller than the number disenrolled, because other people joined the program, offsetting some of the disenrollments).

States had up to 12 months to initiate renewals and 14 months to complete them, but Montana opted to process all of its renewals within 10 months, wrapping up the process sooner than required by the federal government. 8 This accelerated timeframe raised concerns among consumer advocates in Montana, especially since the state already lagged behind most others in terms of how fast Medicaid applications are processed.

Montana prioritized eligibility redeterminations for people who were likely to be ineligible, including those whose income had increased and people who had aged out of Medicaid eligibility (for example, turned 19, or 65). People who are eligible for Aged/Blind/Disabled (ABD). So it’s not surprising that the bulk of the disenrollments in Montana came in the first five months of the state’s unwinding period. 7

People who lost Medicaid could transition to other coverage, either from an employer, Medicare, or a plan obtained in the Marketplace/exchange (HealthCare.gov). CMS reported that by April 2024, almost 22,000 people in Montana had transitioned from Medicaid to a Marketplace plan during the unwinding period. 9

Total Medicaid/CHIP enrollment in Montana stood at about 228,000 people as of mid-2024. This was about 55% higher than enrollment had been in 2013, before Medicaid expansion was implemented. 10

Montana Medicaid/CHIP enrollment peaked at about 330,000 people in May 2023, but dropped significantly during the “unwinding” of the pandemic-era continuous coverage rule (describe above). 7

Montana’s initial Medicaid expansion waiver was effective for five years, from 2016 through 2020. However, it was contingent upon the state legislature reauthorizing the program after June 30, 2019. Without legislative reauthorization, Medicaid expansion would have ended as of July 2019. To avoid the sunsetting of the program, proponents of Medicaid expansion gathered signatures in 2018 to get a measure on the ballot that would have increased tobacco taxes to fund ongoing Medicaid expansion and eliminate the current sunset provision.

Initiative I-185 was approved by the state for signature gathering in April 2018. Supporters then successfully gathered more than the 25,468 signatures necessary in order to get the measure on the ballot, and spending for and against the measure turned it into the most expensive ballot initiative in Montana’s history (tobacco manufacturers funded much of the opposition to the measure, while the Montana Hospital Association funded much of its support). But voters in Montana did not approve the measure in the November 2018 election.

The ballot initiative called for raising the tax on a pack of cigarettes by $2 (to $3.70) and raising taxes by 33% for other tobacco products, like e-cigarettes. It would have compelled Montana to cover the state’s share of the cost of Medicaid expansion using the tobacco tax money. Through 2016, the federal government paid the full cost of Medicaid expansion; states started to shoulder a small portion of the cost as of 2017, reaching 10% by 2020 (it will remain at that 90/10 split in future years). The tobacco tax was expected to generate $74 million per year by 2023, but the expectation was that the state would also have had to come up with additional revenue.

Voters in several other states have approved ballot measures to expand Medicaid, and this approach has been successful in 100% of the states where these measures have appeared on the ballot. But Montana’s ballot measure was different: The state had already expanded Medicaid, and the ballot measure would have permanently funded ongoing Medicaid expansion, instead of relying on periodic funding allocations by the legislature.

Since the ballot initiative failed, the issue of continued Medicaid expansion was in lawmakers’ hands during the 2019 legislative session, and a compromise had to be reached in order to extend Medicaid expansion past the end of June.

H.B.425 was introduced during the 2019 session and simply called for the existing Medicaid expansion program to be extended. That legislation didn’t go anywhere, but H.B.658, which called for a six-year extension of Medicaid expansion along with a Medicaid work requirement, passed and was signed into law by former Gov. Steve Bullock in May 2019. H.B.658 was introduced by Rep. Ed Buttrey, a Republican representing Great Falls who also sponsored the 2015 legislation that expanded Medicaid in Montana.

Under the legislation that was enacted in 2019, Medicaid expansion is approved in Montana through June 2025. To continue the program past that point, lawmakers will need to agree to another extension (or permanently expand Medicaid) during the 2025 legislative session. 2

A lawmaker who helped to create the state’s initial Medicaid expansion legislation has expressed concerns that a federal rule preventing the state from charging Medicaid premiums (details below) could hinder chances for Montana Medicaid expansion to be re-authorized by the legislature in 2025. 11

Since H.B.658 called for a new Medicaid work requirement for non-exempt adults enrolled in expanded Medicaid, the state had to obtain federal approval in order to move forward with implementation. Montana officials submitted their proposed 1115 waiver to CMS in August 2019, seeking federal approval for the work requirement and various other changes, detailed below. The state had planned to implement the work requirement as of January 2020, and between 4% and 12% of the Medicaid expansion population was expected to lose coverage due to non-compliance with the work requirement and/or work reporting requirements.

This was a very tight timeline, as work requirement approvals in other states had taken many months or even more than a year. So it was not surprising when state officials clarified in November 2019 that the work requirement was not going to take effect in January 2020, and could be delayed up to a year.

The work requirement still had not been approved by December 2020, so the Trump administration granted a one-year extension of Montana’s existing Medicaid expansion program. The Biden administration granted another one-year extension in 2021, which continued through the end of 2022.

The Biden administration notified states in early 2021 that approved and pending Medicaid work requirements would be reconsidered to determine whether they fit the objectives of the Medicaid program. By 2021, Medicaid work requirement approvals had been revoked by CMS in every state where they had previously been approved, and Montana’s will not be approved by the Biden administration. (Georgia has since implemented a work requirement alongside a new partial expansion of Medicaid.)

For reference, this is what Montana was proposing, as called for in H.B.658:

Any version of Medicaid expansion that places additional requirements or restrictions on enrollment must be granted a waiver from CMS in order to receive federal funding. Montana’s Medicaid expansion legislation that was enacted in 2015 (S.B.405) deviated from the straight Medicaid expansion called for in the ACA; bill sponsor Ed Buttrey (R – Great Falls) called it the “most conservative plan in the US.”

S.B.405 called for newly-eligible enrollees to pay 2% of their income in premiums, and it also imposes copays for some medical services. In addition, the legislation included a job training and workforce assessment program, aimed at helping enrollees secure a job or move into a better job (this aspect of the legislation was not included in the official waiver proposal that was submitted to CMS in 2015; that is clarified on page 26 of the waiver proposal, and was brought up as a concern by Montana Representative Art Wittich. Work and job training requirements were generally not approved by the Obama administration when included in other states’ Medicaid expansion proposals).

So although SB405 was the law of the land in Montana, the state still needed to get approval from CMS to proceed with its modified version of Medicaid expansion. On July 7, 2015, the state posted the waiver application and began a 60-day public comment period. Montana residents had an opportunity to comment on the proposal online, and there were two public meetings about the proposal in August.

In September 2015, the state submitted its Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration waiver proposal to CMS for review. Official changes to Medicaid eligibility were dependent on federal funding for expansion, which required CMS approval of the state’s waiver. The waiver was approved on November 2, 2015. Expanded Medicaid coverage took effect in Montana on January 1, but eligible residents were able to begin enrolling immediately following the waiver approval.

Montana’s initial Medicaid expansion waiver calls for enrollees with income above 50% of the poverty level (that’s $7,530 for a single individual in 2024) to pay 2% of their income in premiums, which the state said averaged about $26 per month (Montana is one of seven states that obtained waivers allowing them to charge premiums for Medicaid enrollees, although only three — including Montana — continued to charge premiums during the COVID pandemic). Under Montana’s waiver, enrollees with income over the poverty level could be disenrolled if they failed to pay premiums by the end of a 90-day grace period; those below the poverty level were not disenrolled, but their past-due premiums could be deducted from future state income tax refunds.

(Note that between March 2020 and March 2023, states could not disenroll anyone from Medicaid, as one of the conditions for receiving additional federal Medicaid funding. This was true even if a person failed to pay necessary premiums.)

As noted above, H.B.658, enacted in 2019, called for premiums to gradually increase to 4% of income, although they would have stayed at 2% for the first two years a person was enrolled in the program, and premium increases would not have applied to people who were exempt from the Medicaid work requirement. But at 4% of income, premiums for Montana’s Medicaid would have been by far the highest in the country.

And it’s noteworthy that in states that haven’t expanded Medicaid, people with income between 100% and 133% of the poverty level (all of whom are eligible for Medicaid in states like Montana that have expanded Medicaid) can obtain premium-free benchmark plans in the exchange (this is an improvement that took effect in 2021 under the American Rescue Plan and has been extended through 2025 by the Inflation Reduction Act; prior to 2021, people at that income level would have to pay roughly 2% of their income for the benchmark Silver plan). At that income level, a silver plan would include significant cost-sharing reductions, although Medicaid out-of-pocket limits would still be lower.

The increased premium proposal was part of the additional Medicaid waiver amendment that Montana submitted in September 2021. But it was not approved by the Biden administration. Instead, the Biden administration notified Montana officials that they would have to end the Medicaid expansion premiums altogether after the end of 2022.

In 2016 and 2017, Medicaid expansion enrollees in Montana paid a total of $6.7 million in premiums. According to a University of Montana analysis, enrollee premiums cover about 1% of the cost of Medicaid expansion (the federal government covers 90% of the cost; the state pays the rest).

By June 2016, 379 people with income above the poverty level had been disenrolled for failing to pay premiums. In 2017, there were 2,884 people who lost their Medicaid coverage in Montana due to failure to pay premiums. Montana Medicaid enrollees who were disenrolled as a result of non-payment of premiums could re-enroll after they paid their past-due premiums, or at the end of the calendar quarter when their debt is assessed by the state.

As noted above, Montana is no longer allowed to charge Medicaid premiums.

As part of the Medicaid expansion waiver that CMS approved for Montana in 2017, the state would grant 12 months of eligibility to anyone found eligible for Medicaid expansion. If their income or circumstances were to change during that 12 months, they would not lose their coverage.

But the state subsequently enacted a budget that called for the elimination of that rule, and submitted the rule change as part of the waiver amendment proposal that was submitted to the federal government in September 2021. In December 2021, CMS approved that aspect of the state’s waiver amendment.

Until the end of March 2023, Montana (and every other state) could not disenroll anyone from Medicaid for any reason, unless they moved out of state or requested a disenrollment. But starting in April 2023, Montana began applying the new rules to Medicaid expansion enrollees. So if an enrollee’s coverage is renewed and then the Medicaid office receives information within 12 months indicating that the person is no longer eligible, their coverage will end at that point instead of continuing until their renewal date.

That means people whose circumstances change after enrolling in expanded Medicaid may find that they’re no longer eligible for Medicaid and will have to switch to different insurance coverage.

While Montana’s Section 1115 waiver was being reviewed by CMS, the state completed the bidding process to find a private insurer to manage the Medicaid expansion program in the state. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Montana scored highest in the bidding process, and signed a contract in December 2015 to be the administrator for the expanded Medicaid program. BCBS of Montana had been working on infrastructure even before the Medicaid expansion waiver was approved, and began focusing on outreach and consumer education once the waiver was approved.

BCBS of Montana provided care coordination for approximately 19,000 Medicaid expansion enrollees, but the state ended that contract that the end of 2017 in an effort to save money. Montana Medicaid is now managing the program themselves, although they do not get as involved with the care coordination as BCBSMT did.

Medicaid became effective in Montana in July 1967, putting the state around the middle of the pack in terms of implementing the program. And Medicaid expansion took effect in 2016, allowing hospitals, including those in rural areas, to remain solvent. As a result of Medicaid expansion, Montana hospitals have seen a 49% reduction in uncompensated care.

As of June 2011, Montana’s Medicaid program was providing coverage for 60,800 children, 19,900 adults, 10,500 elderly, and 19,600 disabled residents. A total of 178,846 people had coverage in Montana’s Medicaid/CHIP programs as of June 2015, which was an increase of 20% over the 148,974 people who had coverage at the end of 2013.

The increase occurred despite the fact that Montana’s Medicaid expansion didn’t take effect until 2016, due in part to several improvements the state had made to the Medicaid program over the preceding few years. In 2011 and 2012, payment rates for providers were increased. In 2011, the state expanded the existing eligibility rules, and also simplified the application and renewal process. And in both 2011 and 2012, Montana expanded the long-term care portion of its Medicaid program.

By early 2023, after the expanded guidelines had been in place for seven years and the COVID pandemic had been ongoing for three years, total Medicaid/CHIP enrollment in Montana had grown to more than 324,000. The state noted that pre-COVID, enrollment had peaked at about 274,000, and had been “trending downward,” with only about 246,000 people enrolled before the pandemic began. 8 As noted above, enrollment had dropped back down to about 228,000 people after the state finished the “unwinding” process and redetermined all enrollees’ eligibility. 10

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.